Bob Budnitz's memories of Ken Crowe

I came to the Rad Lab (later the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) in the fall of 1967, a brand-new, wet-behind-the-ears postdoc. I had been hired by Don Miller, a high-energy physicist and physics professor at UC-Berkeley who had planned a Bevatron experiment and needed two post-docs (and a couple of graduate students) to pull it off.

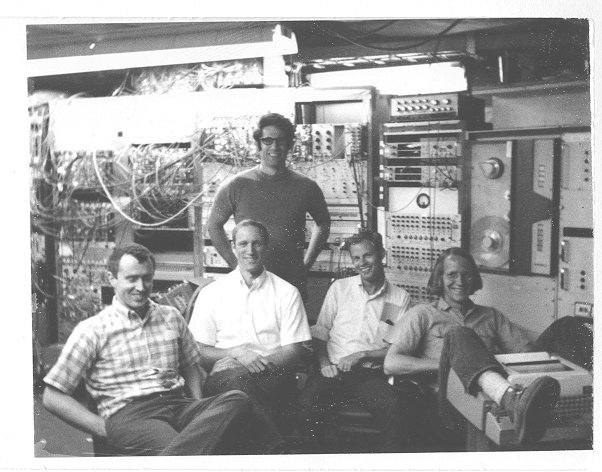

The experiment, which involved a complicated piece of apparatus sitting in a neutral external beam outside the Bevatron, was planning to study the <math>K^0_{\mu 3}</math> "charge asymmetry" in the decay of <math>K^0_L</math> mesons to <math>\pi</math>-<math>\mu</math>-<math>\nu</math> –– the difference between the decay rates to the end states <math>(\pi^+ + \mu^- + \bar{\nu}_\mu)</math> and <math>(\pi^- + \mu^+ + \nu_\mu)</math>. This difference is an indication of CP violation and the effect is tiny, less than half a percent. Don hired me and Bill Ross as the two new post-docs, and then he brought in Bob McCarthy as the student whose PhD would be this experiment, and Jess Brewer as a younger student who would learn the ropes helping with the experiment. We also hired a very fine electrical-electronic technician, Bob Graven, and a handyman-worker Mike Jones. It took us about a year to build the apparatus, and the plan was for the 6 of us, with Don Miller supervising, would do the year-long experiment. But just as we were setting it up in the beam, Miller left! He decided to take a faculty job at Northwestern Univ. in Evanston, Illinois (north of Chicago), and he basically disappeared forever, albeit he did come around every few months to say hello.

Enter Ken Crowe. Our little group's offices in Bldg. 50 were fortuitously in the second-floor wing where Ken and his group resided. So from the start all of us made close friendships with the Crowe group's gang of postdocs and students, although Ken himself was not involved with us much at first. Ken's group was doing experiments at the 184-inch Cyclotron, and they were involved with very different physics and apparatus issues, and very different administrative issues too. So we saw a lot of the Crowe gang informally, although we didn't work with them.

But Don Miller had precipitously departed, and we were sometimes in desperate need of advice from an experienced physicist –– just the sort of advice that a faculty advisor and group leader is there to provide but that Don Miller was now not providing. As a new postdoc, I was often pretty far adrift, way over my head trying to run a complicated experiment without the supervision that was supposed to be the whole point of a postdoc position! (Bill Ross, the other postdoc, was similarly affected. So were the students, McCarthy and Brewer.) And to make matters worse, we learned the hard way that it was going to take more than the 6 of us to run that experiment day-and-night for a year or more. Bluntly, we were short-handed too, and remained so for the duration, a great strain.

Fortunately, as I said, enter Ken Crowe. Ken took the little group under his wing –– and especially took me under his wing. He provided the physics advice we sought, "times ten", but more importantly he provided the intellectual environment and the nurturing environment too that are an essential part of any complicated project like the experiment that we were trying to do. His personality was fantastic, as was his physics insight. As was his way of dealing with each of us individually as a special person, each with his own "issues". Ken basically "saved us" in terms of getting that physics experiment done right, but also in terms of making the experience educational, enjoyable, and useful.

Jess Brewer, in case anybody reading this doesn't know it, went from the entry-level-student job with our Bevatron experiment to become Ken's thesis student at the 184-inch, and later to become one of Ken's closest physics colleagues and friends in muon-spin-rotation/relaxation/resonance studies.

Although after that Bevatron experiment I promptly went on to do other very different things (I became a nuclear engineer), that wonderful two-year-plus experience with Ken Crowe remains a vital part of why it all worked out for me. I for one will never forget it.