The utility of thinking of ![]() as a "ray"

becomes even more obvious when we get away from plane waves

and start thinking of waves with curved wavefronts.

The simplest such wave is the type that is emitted when

a pebble is tossed into a still pool - an example of

the "point source" that radiates waves isotropically

in all directions. The wavefronts are then circles

in two dimensions (the surface of the pool) or spheres

in three dimensions (as for sound waves) separated by one

wavelength

as a "ray"

becomes even more obvious when we get away from plane waves

and start thinking of waves with curved wavefronts.

The simplest such wave is the type that is emitted when

a pebble is tossed into a still pool - an example of

the "point source" that radiates waves isotropically

in all directions. The wavefronts are then circles

in two dimensions (the surface of the pool) or spheres

in three dimensions (as for sound waves) separated by one

wavelength ![]() and heading outward

from the source at the propagation velocity

and heading outward

from the source at the propagation velocity ![]() .

In this case the "rays"

.

In this case the "rays" ![]() point along

the radius vector

point along

the radius vector ![]() from the source

at any position and we can once again write down a rather simple

formula for the "wave function"

(displacement

from the source

at any position and we can once again write down a rather simple

formula for the "wave function"

(displacement ![]() as a function of position)

that depends only on the time

as a function of position)

that depends only on the time ![]() and the scalar

distance

and the scalar

distance ![]() from the source.

from the source.

A plausible first guess would be just

![]() ,

but this cannot be right! Why not?

Because it violates energy conservation.

The energy density stored in a wave is proportional to

the square of its amplitude; in the trial solution above,

the amplitude of the outgoing spherical wavefront is

constant as a function or

,

but this cannot be right! Why not?

Because it violates energy conservation.

The energy density stored in a wave is proportional to

the square of its amplitude; in the trial solution above,

the amplitude of the outgoing spherical wavefront is

constant as a function or ![]() , but the area

of that wavefront increases as

, but the area

of that wavefront increases as ![]() .

Thus the energy in the wavefront increases as

.

Thus the energy in the wavefront increases as ![]() ?

I think not. We can get rid of this effect by just dividing

the amplitude by

?

I think not. We can get rid of this effect by just dividing

the amplitude by ![]() (which divides the energy density by

(which divides the energy density by ![]() ).

Thus a trial solution is

).

Thus a trial solution is

We won't use this equation for anything right now, but it is interesting to know that it does accurately describe an outgoing14.12spherical wave.

The perceptive reader will have noticed by now that Eq. (38)

is not a solution to the WAVE EQUATION as represented

in one dimension by Eq. (10).

That is hardly surprising, since the spherical wave solution is

an intrinsically 3-dimensional beast; what happened to ![]() and

and ![]() ?

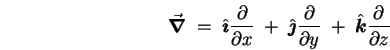

The correct vector form of the WAVE EQUATION is

?

The correct vector form of the WAVE EQUATION is